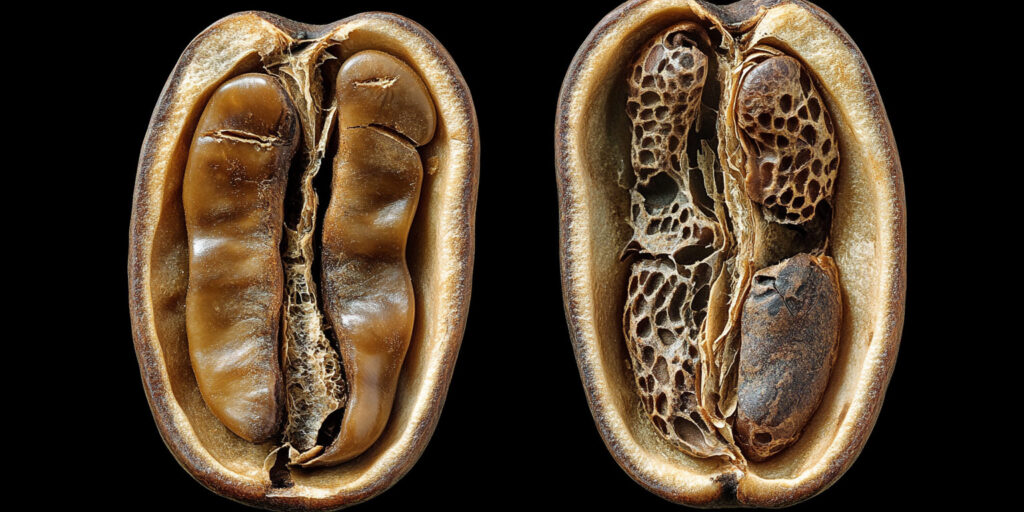

Coffee beans start as seeds inside small, red or yellow cherries that grow on coffee plants. These cherries look more like tiny berries than the dark brown beans you’re used to seeing in your coffee bag.

Here’s what you’ll find inside a freshly picked coffee cherry:

- Outer skin (Exocarp): A firm, often waxy layer that protects the fruit.

- Pulp (Mesocarp): The fleshy part that gives the cherry its sweet, fruity taste.

- Mucilage: A sticky, sugary layer beneath the pulp, crucial for flavor development.

- Parchment (Endocarp): A papery shell that encases the coffee bean itself.

- Beans (Seeds): Usually two seeds per cherry, coated in a thin layer called the silver skin.

At this stage, coffee beans don’t resemble the roasted versions we grind and brew. They’re soft, pale, and have a slightly grassy smell. Before they can become coffee, they must go through several processing steps, including hulling.

What Happens to the Coffee Bean at the Hulling Step?

The hulling process is where the protective layers around the coffee bean are removed, preparing it for roasting. This step can vary depending on the processing method used—dry or wet processing.

Hulling in Dry Processing

In the dry method, coffee cherries are left to sun-dry for weeks. Once fully dried, hulling machines strip away the outer layers, including:

- The dried fruit skin

- Pulp and mucilage

- The parchment layer (which is harder to remove when dry)

The result? Clean, green coffee beans ready for sorting and further processing.

Hulling in Wet Processing

With wet processing, the fruit is removed soon after harvesting. The beans then ferment in water tanks, which breaks down the mucilage naturally. After fermentation, they’re washed and dried before hulling machines remove the parchment layer. This method tends to create a cleaner, brighter coffee profile.

The Final Look: What’s Inside a Coffee Bean?

Once hulled, coffee beans are no longer encased in fruit. However, they still have a thin silver skin, which may remain during roasting and sometimes sticks to the beans after grinding.

Inside, the coffee bean consists of:

- Cotyledons: The main bulk of the bean, where flavors and oils are stored.

- Caffeine and Acids: Contribute to coffee’s bitterness and complexity.

- Cell Walls: Break down during roasting, affecting texture and taste.

When roasted, the internal structure changes, releasing gases and creating the rich, aromatic flavors we love. That’s why dissecting coffee beans helps us appreciate what goes into every cup.